Until the industrial revolution, only the Samurai possessed the secret of creating hard, sharp steel. Above all, he celebrates celluloid as the plastic with the biggest cultural impact: film would have been impossible without it and Miodownik weaves a tale, beginning with the Wild West days of late-19th-century invention, of celluloid's explosive nature (it is a close chemical cousin of guncotton – nitrocellulose or flash paper).Īlso enthralling are the accounts of craft inventions before the scientific age. At the chapter's close, he lists a few iconic examples: nylons, vinyl records, silicone. Miodownik tells a good story: in the case of plastics he even turns in a film script to make the point that they are worthy materials and not, as the 1960s derogatively had it, "plastic, man". Most are useful and aesthetically and culturally pleasing, but he celebrates aerogels – which struggle to find users other than Nasa – for their sheer physical wondrousness: silica aerogel is a spectrally blue substance that seems to blend into the air (it is blue for the same reason the sky is blue – it scatters light), weighs barely more than air (it is 99.8% made of the stuff), and is the world's best insulator: a flower placed on an aerogel block is untouched by a Bunsen burner roaring away beneath it, while graphene aerogel is the world's lightest solid. He's pretty enthusiastic about all the materials he writes about. The odd man out is chocolate, which admittedly has an intriguing technological back-story, but it's there essentially because Miodownik is a chocoholic. The new age is represented by aerogels, graphene and bionic body replacements. I half expected a parade of hi-tech – invisibility cloaks and all – but wisely, he mostly plumps for the longstanding and already humanised materials – steel, glass, paper, porcelain – with plastics, concrete and carbon fibre composites as the representatives from the 20th century. Miodownik has no equations, and his points of reference are often from pop culture and consumerist lifestyles but there are also many nuggets gleaned from history.

Gordon was a great populariser who enlivened his tales of materials with stories of yachting and classical Greece, his other great passions he even gave us the basic equations of materials science.

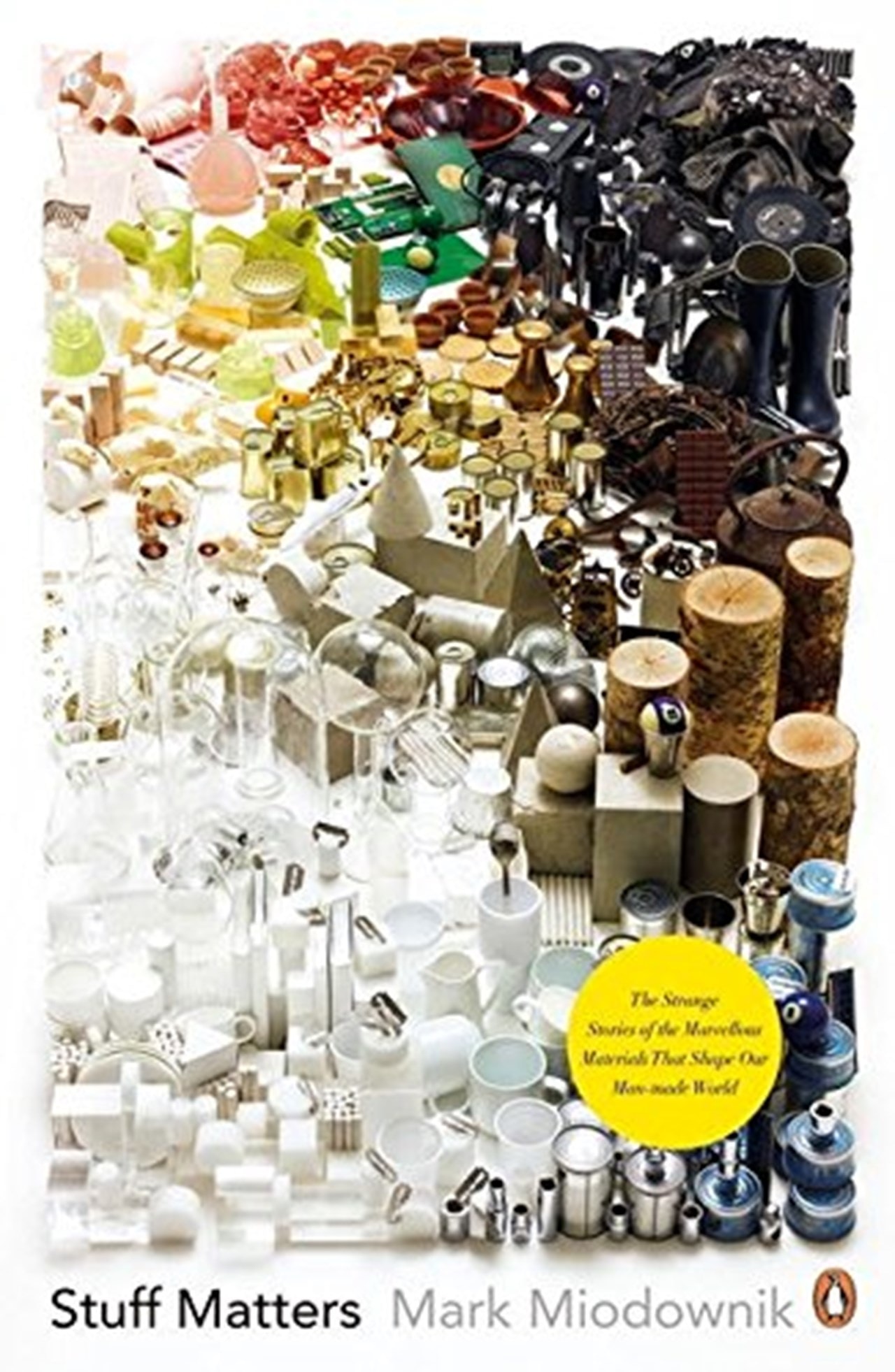

Stuff Matters can be seen as a book in the line of JE Gordon's Structures: Why Things Don't Fall Down and The New Science of Strong Materials or Why You Don't Fall Through the Floor – 1970s classics still in print and cited in Miodownik's further reading list. Mark Miodownik, however, is obsessed with it and, as a TV geek on Dara Ó Briain's Science Club as well as a professor of material science, he's on a mission to re-acquaint us with the wonders of the fabric that sustains our lives.

M adonna called herself the Material Girl and reminded us that we are "living in a material world" but materials, with an "s" – we take that stuff for granted.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)